My idle thoughts on tech startups

Lyft S-1: Kicking Off the Decacorn Bonanza of 2019

This post also appears on NextView’s blog.

I’ve been looking thru S-1s for many years, out of intellectual curiosity to better understand how remarkable businesses work. This includes blockbusters like Alibaba (in three parts) and Facebook but also the likes of Square, Dropbox, Twitter, Blue Apron and going many years back Kayak and Groupon.

There are a variety of quick write-ups on the Lyft S-1 for basic figures like annual revenue, rider growth, or who the largest shareholders are. Here’s one from Pitchbook and one from TechCrunch. I’m going to try to dive a little deeper to assess how good of a business Lyft is and uncover interesting nuggets about the company disclosed in the S-1. If you are interested in a deeper understand like this read on. If you just want my TLDR perspective on Lyft as a business jump to the Conclusion section at the end.

Is Lyft becoming a bigger part of their riders’ transportation spend?

Early on, one of the key questions for all ride sharing companies was the breadth & depth of usage by their customers. When Uber started off as a more expensive “black car” service, people questioned whether it would eventually become a more mass market phenomenon or not. The Lyft and UberX models certainly did that, and shared rides pushed breadth and depth of usage even further as the per ride price point declined.

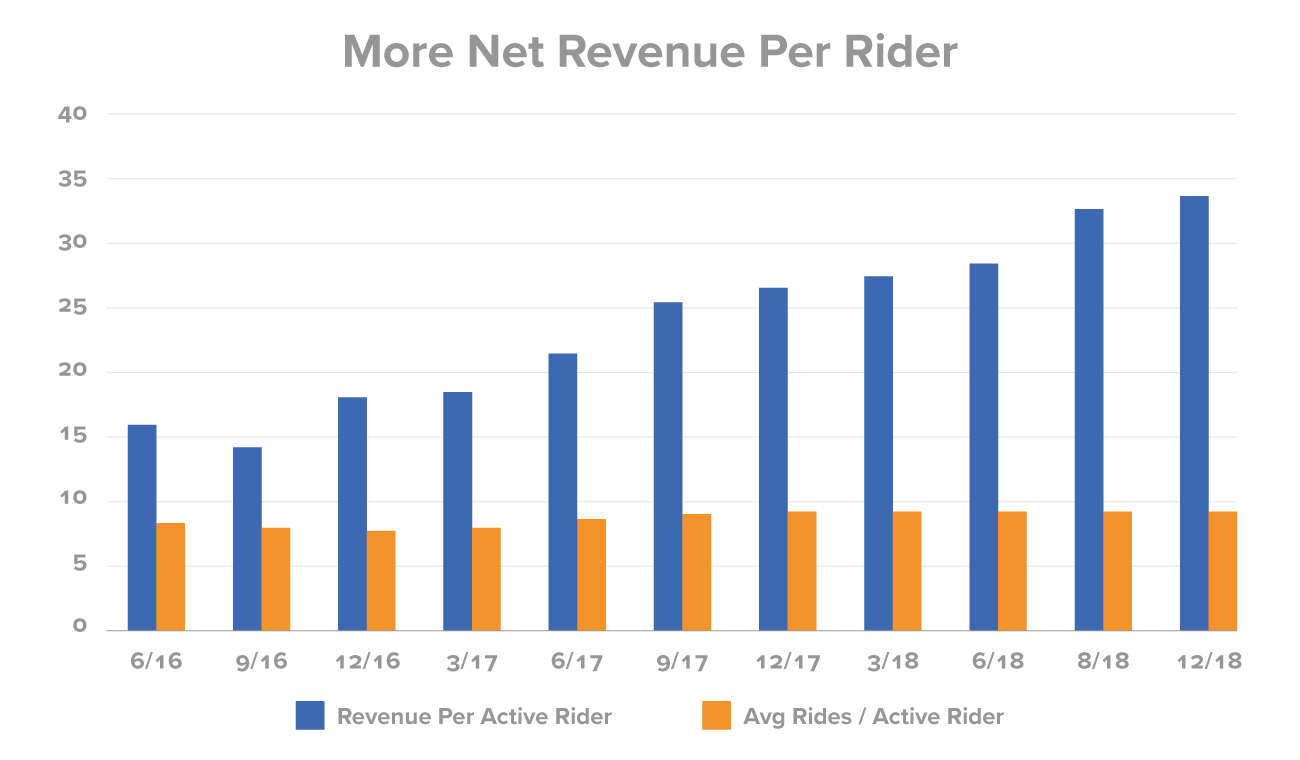

Lyft helpfully provides the number of active riders, total number of rides, and average revenue per rider on a quarterly basis. What struck me was that the average frequency of rides per rider hasn’t actually changed much in the last three years.

Revenue per rider has more than doubled from 2016–2018 (from $15.88 to $36.04 per quarter), but the number of rides per active user has remained right around 9ish per quarter. So it’s not really the case that Lyft’s riders (in aggregate) are using the service more often, but rather Lyft is getting much better at netting more revenue per active rider. If you dig into the Management’s Discussion of the financials, it basically suggests that Lyft was able to increase their commission rate per ride and reduce pricing incentives to both rider and driver thereby extracting more net revenue per ride.

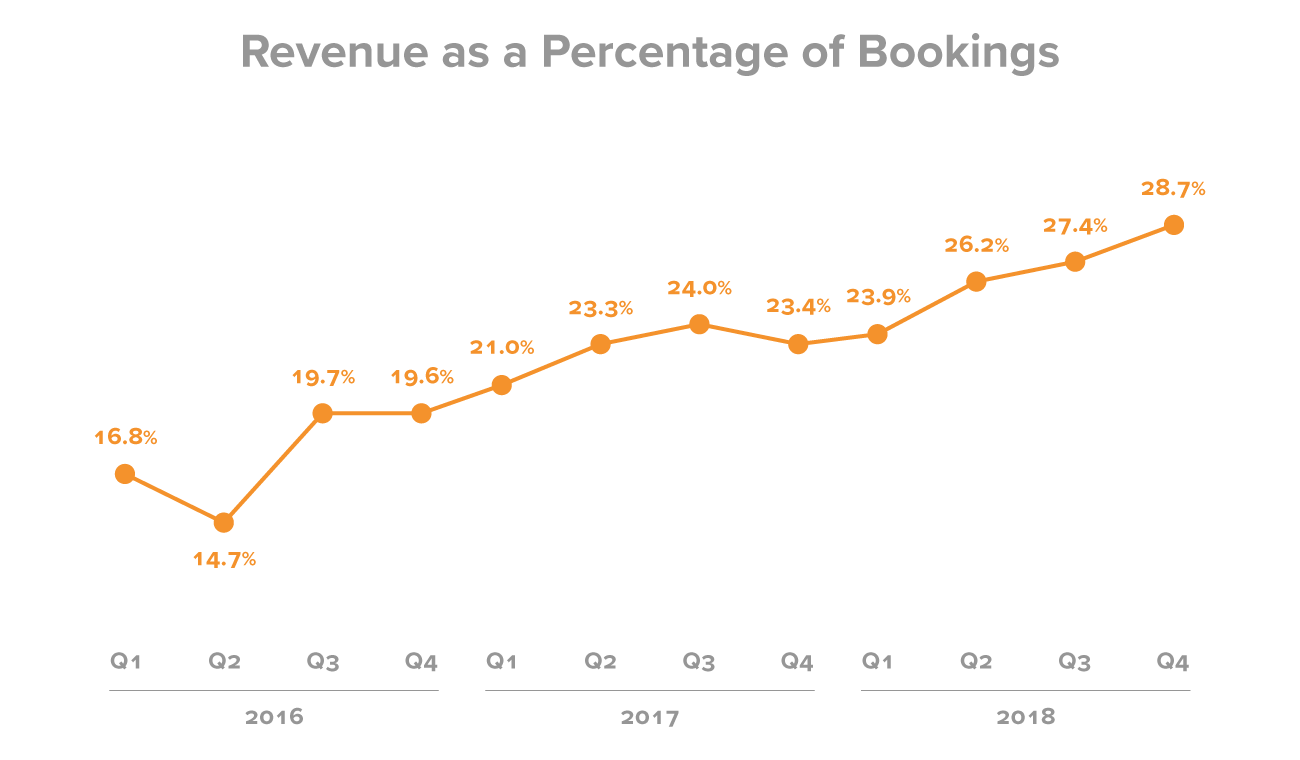

You can see this in a graph they provide of revenue as a percentage of bookings. For clarity, revenue is the portion of the transaction that Lyft keeps and bookings is the total amount of the ride charged to the consumer (excluding tips and tolls/fees). So you can think of bookings as a GMV type figure and revenue as true net revenue to Lyft.

Again basically Lyft has gotten dramatically better at keeping a larger portion of each transaction.

So what about those cohorts?

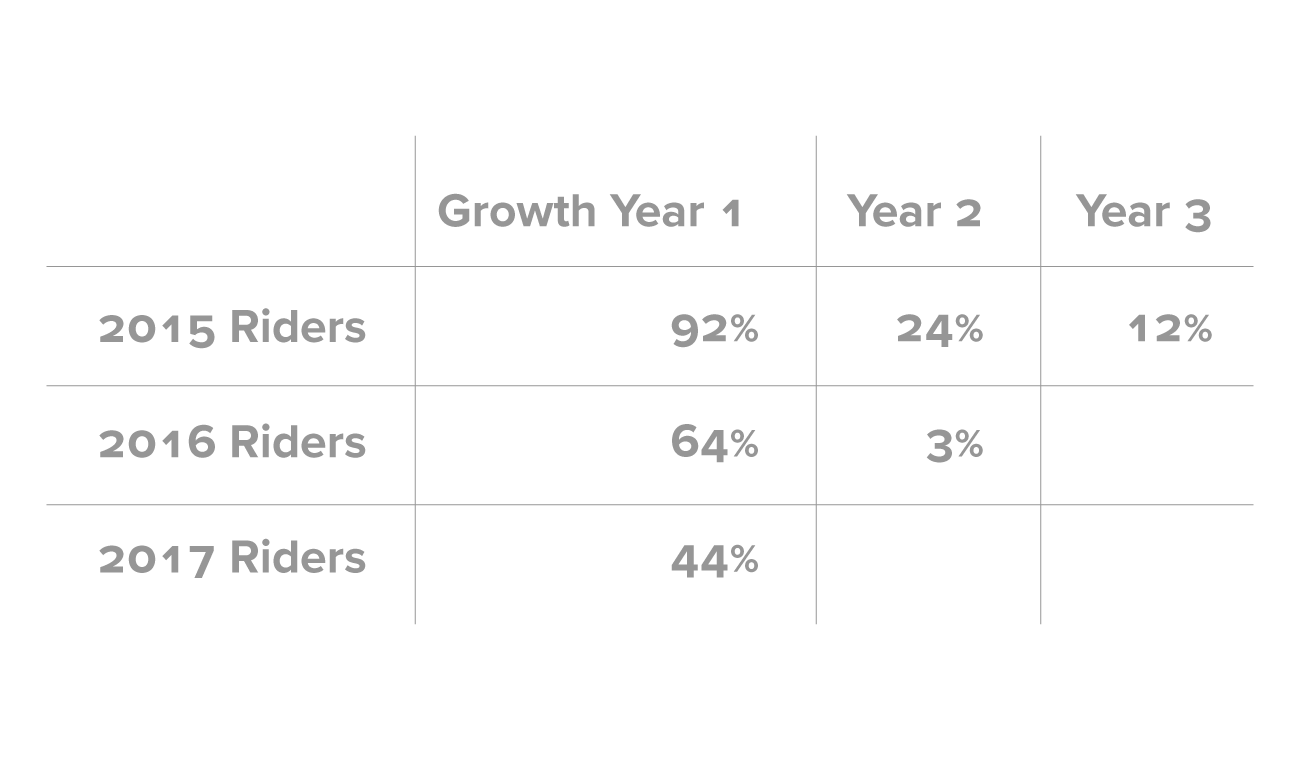

Lyft helpfully provided some very high level cohort data to help us understand the typical evolution of their riders’ usage. Again as I highlighted above, in aggregate Lyft’s users aren’t taking dramatically more rides today then they were 3+ years ago. So there isn’t a paradigm shift going on where overall people are relying on Lyft for more of their transportation needs.

If you look at the yearly cohort level though, you do see a pattern where on average people use Lyft more frequently the longer they are a customer. In their 2nd year as a rider, average users increase their number of rides fairly significantly but then this growth tails off or disappears beyond that.

Additionally we can see that more recent cohorts still grow total rides strongly in their first year, but that newer cohorts are growing rides less quickly than older cohorts. We only have total rides, not the number of riders which are still active in later years. But nonetheless, I think it’s fair to say that Lyft is doing a pretty good job of retaining riders and increasing their usage into their 2nd year of ridership. But it does not appear to be the case as of now that riders today overall rely on Lyft way more heavily than they did 3 years ago.

Does Lyft have a flywheel of money?

One of the powerful features of some businesses is that the strength of their product and brand creates a flywheel whereby they grow revenue perpetually, even without adding new customers. Nothing grows to infinity obviously, but as I noted in my Dropbox S-1 analysis that business had a powerful persistence whereby they increased revenue from existing customers each year simply as an effect of increasing storage consumption per user.

So does Lyft have a flywheel of money?

The simplistic way to do this is to zero out the Sales & Marketing line item in the financials and see what happens. In 2018 Lyft had an EBITDA loss of -$977M whereas their Sales & Marketing spend was $803M. So Lyft would be pretty close to EBITDA breakeven for 2018 if you use this methodology, though again it’s a crude approach and not as useful as digging deeper IMO.

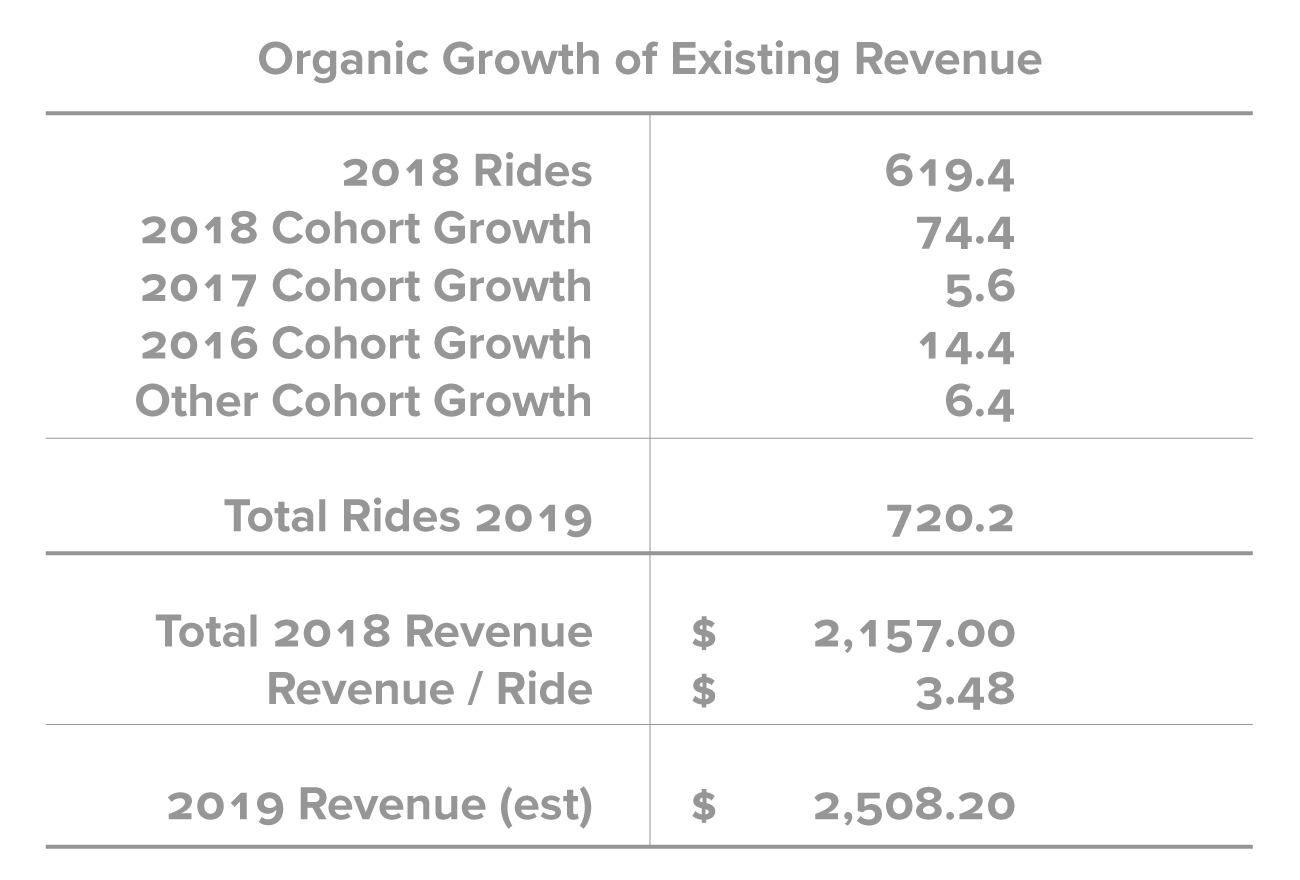

With the pieces of data I picked out above, we can make a somewhat more informed assessment. In reality sales & marketing expenditure is for both acquiring rider customers and drivers, and even if aggregate rides grows without new riders there’s still some ongoing driver churn that requires recruitment spend. I made some rough assumptions about ride growth for recent cohorts based on year 1, year 2, and year 3 growth figures Lyft published and assumed older cohorts grew rides 5%. I also assumed that revenue per ride, which has risen substantially in the last several years, remains similar to 2018.

So there is a bit of a flywheel here, as revenue would grow something like 16% over 2018 just on existing riders based on my assumptions above. Lyft theoretically could be EBITDA profitable if they cut sales & marketing spend substantially (but not to zero) and didn’t add any new riders in 2019. In reality it wouldn’t make sense for the company to do this, and Lyft would probably grow some organically even with out rider marketing spend. But understanding how the existing business grows and could be profitable is useful in assessing the overall strength of the enterprise.

Lyft’s Biggest Cost “Driver” Isn’t the Driver

As described above, what Lyft recognizes as revenue is their portion of the transaction they keep so it excludes the payment to drivers. To be clear, the portion of the transaction the driver keeps is the largest absolute amount… Lyft booked roughly $8 billion worth of rides in 2018 and recognized approximately $2.1 billion in revenue.

But given they’re essentially recognizing “net revenue”, Lyft’s cost of goods (COGS, aka cost of revenue in S-1) is composed primarily of insurance, credit card processing fees, and software/tech hosting costs. Insurance is far and away the largest cost driver. While the S-1 doesn’t break these out individually in COGS, reading through the footnotes we can glean that insurance is the largest of these cost drivers. Lyft essentially operates it’s own internal insurance entity, so they deposit funds into an insurance trust periodically and then recognize expenses when claims are paid out.

Overall Lyft is driving their COGS down, from >80% of revenue in 2016 to roughly 57% of revenue in 2018. So they’re increasing the overall percentage of the transaction they take as revenue while simultaneously driving down their direct COGS to support that revenue. This bodes well for Lyft’s ability to continue to drive towards profitability in the coming years, even though they remain an unprofitable (albeit still rapidly growing) company today.

Conclusion

So what’s the bottom line? By breaking down rider economics, transaction splits, and cost drivers we have a richer understanding of Lyft as a business. This is a company which is currently unprofitable, but still growing at 100% YoY and it appears to have a modest “flywheel of money” by which its existing customers will continue to drive incremental revenue. Lyft is also taking an increasing % of each transaction and reducing its costs, so my conclusion is that this company has a pretty clear path to profitability.

How Lyft will be valued by public markets is a bit of a wild card. It appears they will beat Uber to IPO, so helpfully they can frame this new category of “transportation as a service” in the minds of public equity investors. Lyft has done a very good job of gaining market share in the last 2–3 years, which they estimate at 39% of ridesharing in US. But they remain #2 to Uber in the US and with a much more limited global footprint to their rival. When Uber’s S-1 drops, I will be curious to see what they may disclose in terms of rider frequency and revenue per ride.

The other overarching question about how Lyft will be valued is the embedded risks and upside. In the US, the regulatory framework has reached a fairly stable environment after a bumpy start when ridesharing began, so I see this as less of a risk today. When autonomous vehicles become a reality, there’s also a potential for companies like Lyft to further gain market share and reduce costs. But it’s not a given that Lyft will be a winner in an AV world, and it’s still quite uncertain how many years we are away from true Level 4/5 autonomy in the US.

But overall this is a solid business, helping pioneer a massive shift in personal transportation which is one of the biggest slices of the economy. I suspect Lyft will have a good IPO and will achieve profitability and continued growth in the coming years.